May 2011, Vol. 66 No. 5

Features

HDD Project Completed In Cascade Mountains

Directional drilling installations that a dozen years ago would have been considered impossible are routinely performed today. Projects in difficult conditions that made industry news then are commonplace now.

Broader applications of horizontal directional drilling (HDD) is the result of the combination of better equipment and downhole tools, understanding of the use of drilling fluids and the knowledge and experience of the crews who understand how to use these technologies to maximum advantage.

There always will be “can’t-be-done” jobs that will be completed by enterprising drillers, and there’s a small group of HDD specialists who seem to relish tackling such projects.

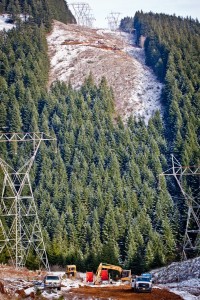

One of the most difficult and impressive recent HDD projects was completed this winter high in the Cascade Mountains of Washington.

General contractor Robinson Brothers, Vancouver, WA, was responsible for relocating approximately eight miles of aerial fiber optic cable. It was failing due to the harsh weather and was to be placed underground. HDD segments were subcontracted to Apex Directional Drilling. The cable route went up and down steep, heavily-wooded mountainsides and crossed canyons, some of which contained streams and lakes. Solid and fractured basalt encountered in drilling ranged in hardness from 20,000 to 50,000 psi.

Two, 2-inch diameter HDPE ducts to hold fiber optic cable were placed in the ground. Approximately five miles of the route was plowed, with three miles put in the ground by directional drilling.

“It was clear at the beginning that these would be extremely challenging bores to complete,” said Apex Directional Drilling President Mike Lachner. “This was a high-profile project and it attracted a lot of attention and interest.”

Equipment choice

The Apex bid costs were based on using a 100,000-pound pullback drill unit with a dual-pipe mechanical drilling system, rather than a larger machine with a mud motor. Not employing a mud motor eliminated the need for support equipment required for that technology and greatly reduced the quantities of drilling fluid necessary.

“That we would attempt these bores with this equipment probably raised some eyebrows,” said Lachner. “I’m sure there were those who didn’t believe it could to do the job in these conditions. However, we are confident in our capabilities. We like difficult projects, but we don’t undertake anything we aren’t confident in completing. Although we’re a young company, our management and personnel have many years experience in HDD, including many difficult projects, and we’ve already established a reputation for doing jobs other contractors don’t want to take on. We have experience with the mechanical drive system on smaller machines and were comfortable the 100,000-pound model could do the job.”

The Ditch Witch JT100’s All Terrain (AT) dual-pipe mechanical drilling system — Lachner calls it a mechanical mud motor — employs an inner rod to drive a rock bit, and the outer pipe uses a bent sub to steer the downhole tool for drilling pilot holes and provides rotary torque for the hole opener during backreaming. It is designed to delivery maximum downhole horsepower to the bit while operating with low volumes of drilling fluid.

Apex handled the job as a design/build project, performing a turnkey operation that included detailed planning of the bores and completion of each HDD installation.

“Planning each bore was critical,” said Lachner. “With the severe downward angles, it was essential to level off at exactly the correct point and then start up the opposite slope at exactly the right spot to hit the projected exit point. Profiles were critical, and we had to maintain a 40-to-45-foot depth because our plan was to use walk-over tracking equipment and if we went deeper, we could lose tracker signal.”

Apex’s JT100 unit had been doing long-haul work on the east coast, and was brought to Washington for the mountain project. A five-man crew began work in October 2010.

Logistical nightmare

The logistics of getting the drill unit, support equipment, supplies and personnel to set-up locations was complicated and difficult.

“Some roads had to be built, and launch pads constructed and maintained,” said Lachner. “Equipment was hauled over mountain roads with a D8 Caterpillar dozer. On some of the bores, it was seven miles from a paved road to the set-up location. The two-inch duct was on reels, and the D8 Cat pulled reel trailers to work sites. Crew members and supplies were brought in and out with a 6×6 ATV.”

For each pilot hole, 6½ -inch tri-cone bits were used. To keep pilot holes open during product pullback, a 6-inch Rockmaster backreamer was connected in front of the pipe string.

A Ditch Witch 752 walk-over tracking system was used in conjunction with a TMS bore planning system, a Windows-based bore management tool to plan the bore, monitor its real-time progress and print an as-built map of the completed installation.

Throughout the project, weather made working conditions difficult.

“We got started in October 2010,” Lachner said, “and the snows came in November. From then through completion of the last bore in February 2011, we worked in winter conditions. With heavy winds and freezing temperatures, along with significant snowfall we were forced to bring in all-terrain vehicles to mobilize in and out of the drill sites each day. The location furthest out was roughly seven miles from the base of the mountain.”

Keeping equipment from freezing and supplying machines with water and fuel were issues, also.

“We had to carry in diesel fuel in portable slip tanks and gas cans over the course of each day,” Lachner continued. “With water trucks having limited access to our drill sites, we had to schedule each day based on their mobility to us. We ran Cat D9 dozers all day everyday up and down the mountain roads to keep them clear enough to drive on and even at that our 4×4 rigs were not always able to maneuver up and down the steep hills. We transported all our equipment and tooling to and from each drill site on trailers with large excavators and dozers because the access roads, even when clear, were too steep and curves were too sharp for trucks to travel.”

Constant high winds through the mountain canyons made it necessary for continual maintenance on tents and shelters built to cover fluid mixing systems and reclaimers. High-grade propane heaters and large containers of propane were used to keep them warm in the freezing temps. Snowfall at its peak was about six feet with drifts as high as 10-12 feet on both sides of the bore sites.

“At times, we had to move snow to keep equipment from being buried, and we actually had to make new roads through the snow for access to our equipment,” Lachner added.

Environmental restriction

There were also environmental restrictions that had to be observed.

“Trees with trunks larger than eight inches in diameter could not be removed,” he explained. “In addition we had time constraints requiring the project to be completed by February because work could not continue during the spotted owl mating season”.

The project was finished on-time and on budget. Lachner credited successful completion of the project to careful planning preparation before work began and the experience and performance of crew members who made each installation precisely as planned.

“Each bore was different and required adjusting mud flows and pressures and other variables,” said Lachner. “A lot of things had to come together for everything to go as it did.”

The Apex project manager was Jason Stephenson and Ryan Zimmerman operated the drill unit. President Mike Lachner was actively involved in operations throughout the project.

Based in Damascus, OR, Apex works on a national level serving multiple clients. The company currently owns eight HDD units ranging in pullback from 30.000 to 100,000 pounds. Soon after completion of the Cascade project, a second 100,000-pound unit was purchased.

In retrospect, would Apex take the job again?

“Absolutely,” Lachner answered. “We love ‘impossible’ jobs.”

Six ‘Impossible’ Bores

Each of the six bores made by Apex Directional Drilling in Washington’s Cascade Mountains contained high grade changes and steep slopes, and ranged in length from 1,100 feet to 2,300 feet. One bore crossed a lake with depths at 45 feet and spanning 965 feet, then up a vertical slope of about 650 feet. The other five bores were land and canyon crossings starting from the high sides of the canyons and drilling down to a level pitch at the bottom, drilling across the canyon, and elevating to the exit point on the other side. Each bore had its own engineering issues that needed to be addressed so there was no general format that could be used for all six.

Apex president Mike Lachner describes each bore:

Bore 1 was approximately 1,700 feet going under a heavily wooded canyon. We started drilling down at a minus 36 percent grade, shot down roughly 350 feet, and leveled off to drill across the bottom of the canyon spanning another 300 feet. We started at an upward angle reaching a positive 70 percent on a 200-foot incline and steered a hard left turn to the vault location at the tower.

Bore 2, called the Bluff Bore. The length was 1,500 feet. We started on the low end of the bore and went down a steep grade of minus 45 percent for approximately 300 feet, leveled off under the canyon and back up roughly 1,050 feet to the exit at a vault location, including a grade change at 650 feet reaching a positive 80 percent grade up the side of the mountain.

Bore 3 was the reservoir shot. The drill rig was at the bottom on a level grade with the lake. We drilled down to a 45-foot depth and leveled off to span 950 feet under the lake. We then bored uphill about 1,158 feet following a plus 60 to 75 percent grade, depending on the bore layout, with an elevation change of 800 feet and notched out the hillside to stage tooling and pull product. This bore was one of the two extremely severe bores considering the grade changes required.

Bore 4 was 1,200 feet under a canyon, but the layout required a set-up location that prevented drilling directly across in a straight line — the slope to the bottom was too steep to meet our bend radius. With plenty of room in our right-of way, we chose to drill around the outside of the canyon keeping within our running area. This one was a little easier with a minus 24 percent grade. We shot this bore from the side instead of setting up directly under the power lines. Upgrade to the exit point was plus 48 percent.

Bore 5, the timber bore, was across a canyon filled with thick forest that had to remain undisturbed. The set-up spot was on the side with the most room for equipment staging with both sides being about the same elevation. We shot down at about a negative 65 percent and slowly began to level off and hit the bottom of the canyon level in approximately 450 feet. We began a plus 24 percent up grade about three quarters of the way across the canyon to hit the bank on the uphill side that increased to a positive 80 percent to follow grade up the hill. We drilled out roughly 1,300 feet to the exit point. This bore had an elevation change of 245 feet to the bottom of the canyon on the machine side and about 280 feet of change to the exit point.

Bore 6 was called Dog Creek. We set up on the top side of the bore drilling down following minus 65 percent grade with an elevation drop of 700 feet. We shot down about 1,300 feet to level off to drill under the creek which was about 60 feet across with fast-moving water about three-feet deep. Past the creek, we began uphill at a plus 40 percent grade with a more gradual incline for about 900 feet with elevations reaching 300 feet. This was the project’s longest bore due to the ground conditions, and the grade changes required more distance to maintain the bore profile.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

Apex Directional Drilling, 503-427-2230, www.apexdirectionaldrilling.com

Ditch Witch, (800) 654-6481, www.ditchwitch.com

Comments